It

was a low-tech engineering marvel with a lethal purpose. North Vietnam’s (NVN)

shadow highway to the south steadily and stealthily delivered men and materiel

to the battlefields of South Vietnam (SVN). Its immense success was reflected

in admiring nicknames coined by Americans tasked to shut it down. Because of

Ambassador Harriman’s illusion of a neutral Laos through which the shadow

highway passed, US Saigon Embassy personnel cynically referred to the Ho Chi

Minh Trail (the Trail) as the “Averell Harriman Memorial Highway.” A Marine

general called it the “Ho Chi Minh Autobahn,” while a Green Beret who had

reconnoitered the route said that at times it was “like the Long Island

Expressway – at rush hour.”

What

Washington dubbed the Ho Chi Minh Trail (actually its official name was the Trường

Sơn Strategic Supply Route) had ancient origins in the Annamite Mountains and

jungles of Southeast Asia along the western border of what became SVN after the

defeat of the French colonialists in 1954. It had long been a loosely connected

network of primitive paths and trails through the wilderness trod only by

aboriginal tribes inhabiting that sparsely populated, inhospitable area. Only

in the late ‘40s during the long Vietnamese war for independence against the

French did the network take on some semblance of a logistical trail system. The

Viet Minh, the communist-nationalist guerrilla army created by Ho Chi Minh,

used the system of trails as a clandestine route for moving fighters from the

northern area of France’s Indochina colony to the Mekong Delta in the south

below Saigon.

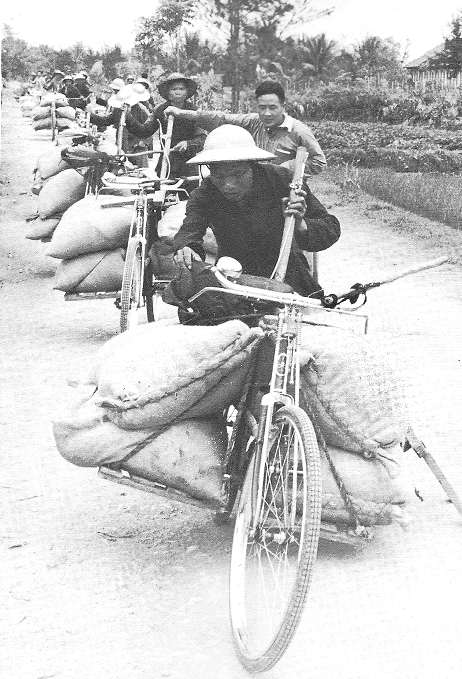

After

’54, the system fell into disuse, temporarily as it turned out. In ’59 the

Communist Party of NVN decided to significantly support the ongoing low-level

guerrilla insurgency against the government of SVN, and the Trail again saw

military traffic. Because the early Trail involved climbing steep, heavily

forested mountains and traversing rough jungle terrain, elephants were

initially used to carry the heavy supplies. Eventually the preferred vehicle

for transporting larger-caliber weapons, ammo, and foodstuffs became specially

reinforced bicycles pushed, not ridden, by porters. Frames were strengthened,

handlebars fixed with a long steering stick, and a pole for stabilizing the

bike arose from the seat. Fully loaded, the bikes carried several hundred

pounds.

Bike

porters on the Ho Chi Minh Trail

After

’65 when the war escalated on both sides, the Trail was widened, and heavy duty

Chinese army trucks replaced bikes. A truck-relay system was developed with

designated individual sections of the Trail responsible for keeping their own

fleets on the road. An underground pipeline was laid to provide fuel to the way

stations along the Trail. Early on, Pentagon planners calculated that only as

few as 20 truckloads of cargo a day, a fraction of the truck traffic on the

Trail at any one time, had to get through for the NVN to meet its supply

requirements in the south. By then the Trail had become a dual system – roads

safe only at night for the trucks, while troops marched off-road by day, often

having to cut trail as they went.

Throughout

the Trail’s active service from ’59 to the fall of Saigon in ’75, North

Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops moved along the route with heavy packs weighing as

much as 85 lbs that contained food, clothes, and ammo for both the long journey

and, ultimately, the SVN battlefields. To reach the Saigon-Mekong Delta region

in ’64 by foot took five months.* Even later, after the system was considerably

engineered and improved, the full trek still lasted as long as six weeks. To

say that NVN’s ‘long march’ was arduous and tested the limits of human

endurance would not be an exaggeration.

On

the Trail through the mountains

Not

all the NVA troops that moved as units were destined for the Mekong theater of

operations. The Trail, which paralleled SVN’s border through Laos and Cambodia,

had various ‘exits’, much like an American superhighway. The first exit was

just below the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) separating North and South Vietnam for

units assigned to the Hue-Phu Bai sector, the area where brother Jeff Sharlet

served in ’64. Although trail time was shorter for troops headed for that

sector, they still had to climb over a rugged mountain range in northeast Laos

to reach their destination.

While

the Trail was NVN’s conduit for matching US troop levels in the south with NVA

combat regiments and battalions, it was maintained by a separate command

consisting of tens of thousands of engineering troops, anti-aircraft units,

infantry for ground security, and huge numbers of young women volunteers

assigned to roadwork – a highly dedicated and efficient combat support force

stationed along the myriad byways and alternate routes of the 8000-mile road

system.

The

Trail and its ‘exits’

For

the NVA troops trekking down trail, the terrain, predators, disease, and

weather added to the ordeal. The foot trails were stony, rest areas rough-hewn,

and the rainforests through which they passed either suffocatingly hot and

humid or rain-drenched, perpetually damp, and steamy during monsoon season.

Insects and jungle creatures plagued the transiting soldiers. Mosquitos swarmed

in clouds; leeches abounded, whether in water crossings or dropping from trees;

and poisonous snakes were ever a danger – everyone carried anti-snake venom,

which had to be self-administered within three minutes of a bite. Many soldiers

died enroute from disease – malaria, typhoid fever, amoebic dysentery, and many

other infectious diseases, even plague, were endemic.

However,

in terms of sheer ferocity and a staggering death toll, nothing along the Trail

matched the US Air Force’s bombing and strafing campaign. When ‘Rolling

Thunder’ was launched during spring ’65, Washington believed a relentless

bombing campaign of NVN would ‘persuade’ the Communist regime to sue for peace

or at least cause them to cease and desist stoking the southern insurgency with

streams of men and supplies down the Trail. As the fighting intensified and US

illusions about NVN’s commitment and steadfastness began to fall away, the

strategic objective shifted to shutting down the pipeline feeding the Viet

Cong’s (VC) insurgency against the SVN regime. In military-speak, the objective

became ‘interdiction’ to prevent cross-border infiltration from NVN via Laos

and Cambodia.

For

this purpose, the hi-tech might of the world’s greatest military power was

brought to bear on the Trail. The battle in the air against the enemy became a

veritable separate, secret war apart from the ground war in SVN where GIs and

Marines were going head to head with the VC and NVA battalions from the DMZ to

the Mekong Delta. The air war was concealed from Congress as well as the

American public because a large percentage of the thousands of air strikes were

against the Trail in nominally neutral Laos and Cambodia.

At

the outset prop-driven Douglas trainers were deployed to bomb and strafe enemy

formations spotted along the shadowy trail. As the flow from the North

increased, the air war escalated when Phantom jets armed with rockets and

napalm entered the fray. B-52 bombers from Guam, designed for Cold War

intercontinental warfare with the Soviets, were added to the order of battle.

Carrying enormous bomb loads, the bombers cruised unseen seven miles up from

where their deadly cargoes of 750 lb bombs were dropped from map coordinates.

B-52s

over the Trail

As

part of the Pentagon’s evolving electronic warfare, a device was created for

detecting the presence of humans invisible in the impenetrable jungle below

from the air. Colloquially known as ‘people sniffers’, the device was slung

under a helicopter which reconnoitered suspected Trail areas, picking up the

scent of urine. Coordinates would be transmitted, and perhaps the most

destructive air weapon of all would be called in – a converted C-130 cargo

plane nicknamed ‘Spooky’ because, being slow and flying at low altitude, it

operated at night. Bristling with

automatic rapid-fire Gatling-type guns, Spooky would fly over the identified

area, sometimes at only 1500’, and literally shower the jungle below with lead

at the rate of 15,000 rounds a minute, eerily lighting up the night with red

tracers.

One

might think such overwhelming power would prevail, would have defeated NVN’s

effort to sustain the war in the south. On the contrary, through surprising

feats of Engineering 101 and often simple, even primitive countermeasures, the

Trail remained a busy military thoroughfare as the vital route to the ground

war in the south and ultimate victory in ’75. To counter relentless air

attacks, the NVA positioned anti-aircraft guns at critical chokepoints on the

Trail, ensuring that US bomb runs were not cost-free. Later, batteries of

Soviet surface-to air missiles (SAM) were added, greatly increasing Air Force

fixed-wing losses. In the course of the separate war over the Trail thousands

of NVA trucks were destroyed and heavy casualties sustained, while the US lost

500 planes with their air crews.

Air

attacks on the Trail were most effective against bridges over the many rivers

that had to be crossed. Engineering crews could put pontoon bridges in place

relatively quickly, but they too would be knocked out the next day by prowling

Phantoms. For this special challenge to Trail traffic, combat engineers came up

with a couple of workable, low-tech solutions. The first was a cable bridge,

but one without a roadway. Two strong cables would be strung across a river

invisible from the air at water level a truck-width apart. When a truck convoy

arrived at a crossing, the tires were removed, the rims aligned on the cables,

and the trucks driven across, and refitted with tires on the opposite bank.

This

bridging technique worked well, but was time-consuming, so another equally

simple but even more amazing solution found. A pontoon structure called a

‘peek-a-boo’ bridge was rigged out of the inner tubes of truck tires, and

powerful pneumatic pumps were hidden on each side of a waterway. When not in

use, the bridge would be concealed by deflating the tubes and letting the

structure sink and float beneath the water’s surface. Upon arrival of the

trucks, the pneumatic pump would inflate the tubes, the bridge would emerge

from the depths, and the convoy would pass over it.

Road

repair from bomb damage, a constant, was essentially a no-tech job. Without the

availability of bulldozers, the largely female road crews posted along the

Trail filled bomb craters overnight with just picks and shovels. Occasionally,

when a stretch of trail was being repeatedly targeted, the engineers would cut

an alternate route below the triple canopy jungle, thus hiding it from the air.

Often this involved cutting down trees and clearing brush, but when the NVA

realized that their hi-tech adversary had airborne means for detecting foliage

decay, they changed tactics. Trees and bushes were instead carefully dug up and

transplanted elsewhere, an elementary gardening procedure.

However,

the NVA’s most primitive but effective countermeasure – and a devilishly clever

and amusing one too – was its diversionary response to the vaunted airborne

people sniffers. Pots of buffalo urine were hung in the trees in areas away

from the Trail causing the planes to release their munitions harmlessly on

empty stretches of jungle. Still, the relentless air attacks never ceased.

After

the Communist Tet Offensive of ’68, Creighton Abrams replaced General Westmoreland

(Westy) as overall US commander and inherited not only a grinding ground war,

but also the shadowy, hotly contested air war over the Trail. The interdiction

campaign remained his major preoccupation right up to the final days of active

US involvement in the Vietnam War late ’72. Transcripts from Abrams’ regular

briefings clearly indicate that in spite of the best efforts of a superpower,

interdiction had remained a frustrating and elusive objective. In late ’70, his

deputy commander for air operations conceded that the scope and effectiveness

of the Trail had increased:

Over

the past year we’ve seen a continual increase

in the road network,

the trails, the alternate route

structure … which gave the

enemy many options

in terms of moving his equipment and supplies

….

[The

NVA’s dispersal of their trucks] has been

accomplished

beautifully, they move at night, they

move at regular

predetermined times, they move to

one place, stay and

hide, unload, pick up another

truck and move on down, hiding

in the [jungle]

canopy, it’s just an extremely difficult

problem.**

As

American involvement in the war was winding down 18 months later in ‘72, it was

evident that NVA infiltration had trumped US interdiction. As a frustrated

General Abrams exclaimed to his staff: “it’s a more or less continuous thing –

you know, they just keep a-coming.”***

Years

after in post-mortems on the war, a senior North Vietnamese officer conceded

that US air attacks, especially Spooky’s saturation strafing, had hurt them

badly, while Westy’s deputy stated flatly in an interview that the fact that

the “Ho Chi Minh Trail was never closed”

was a major factor in the failure of the US mission in Southeast Asia.****

*J

Zumwalt, Bare Feet, Iron Will (2010), 232

**L

Sorley, ed, Vietnam Chronicles: The Abrams Tapes, 1968-1972 (2004), 495

***Ibid,

818

****Quoted

in R McNamara, In Retrospect (1995), 212

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.