In

the time between the world wars, our father, like so many Americans, had visited

Cuba’s exotic capital in the interwar period. He was in Havana in 1930 during

the country’s heady Republican Period, but decades later my brother Jeff and I

had only passing awareness of revolutionary Cuba of our own time. We’d both seen the family photo of Irving as a

young man – he was 21 – dressed to the nines with a good looking blonde at the

bar in Sloppy Joe’s – the famous celebrity hangout on Cuba’s Golden Riviera.

Irving Sharlet

(l), our father, in Havana, 1930

Irving

had grown up in comfortable circumstances; he had some money and was something

of a playboy. At the time, Prohibition reigned as the law of the land in the

States. To get a drink without a password in a back alley speakeasy,

well-heeled Americans would sail off to Europe or head to the Caribbean to

relax with a highball in fashionable public places. Sloppy Joe’s was one of the

in-places, just off-shore so to speak, where one might see John Wayne or Clark

Gable or even Cuba’s most famous North American visitor, Hemingway, down the

bar.

Decades

afterward during the postwar period when dramatic changes began happening in

Cuba, the island country was on the periphery of our young lives. Jeff in his

short life – he died at 27 – had been heavily involved with Vietnam. Serving

there early in the growing conflict, he later became an international leader of

GI opposition against the war. I became an academic, a specialist on the Soviet

Union, where I had studied and visited periodically. I spent most of my adult

years teaching and writing about the country.

Still,

as the Cuban Revolution emerged in the ‘50s and consolidated in the early ‘60s,

quite serendipitously Jeff and I bore witness to some of the salient moments of

the island’s transition from a popular Caribbean tourist destination to the

epicenter of the global Cold War. Cuba first came to my attention unexpectedly in

late fall ’56. In the phrase of the day, I was fulfilling my military

obligation in the army.

___________________________________________________________________________

The rebellion in Cuba is over, and students of foreign affairs can now

give themselves again to Hungary and the Middle East.

_________________________________________________________

I

was fortunate, having been assigned to a congenial posting for a year of study

at the Army Language School (ALS) on the sunny California coast. I was being

trained in a Slavic language, my only duties six hours a day of class and a

little homework. At lunch break, I always had the latest issue of the airmail

edition of the British paper, Manchester

Guardian, in my back pocket as I waited in the chow line. Reading it was a pleasant

respite from the morning’s grammar lessons, pronunciation drills, and

vocabulary tests.

One

noontime I was glancing through the early December ‘56 issue of the Guardian. Hungary and the Suez Canal

were the lead stories. The Soviets had just bloodily crushed the Hungarian

Revolution while the Israeli, British, and French forces had defeated the Egyptians, whose nationalization of the Canal had touched off a brief but fierce war.

Perusing

the back pages, my eye fell on an unfamiliar story, ‘The battle for Cuba’, with

a dismissive opening line, “The rebellion in Cuba is over, and students of

foreign affairs can now give themselves again to Hungary and the Middle East.”

Reading on, I found a lighthearted account, rife with British irony, of a

hapless invasion of the island by a band of Cuban revolutionaries sailing from

Mexico.

As

I would learn a few years later, the Guardian

had some of the key details wrong, but it was right on the end of the affair –

the armed forces of the dictator Batista had quickly routed the invaders –

killing or capturing most of them on the beach.

The

invasion group – 82 of them – had arrived offshore aboard a yacht perilously

overloaded with men, weapons, and ammo and leaking to boot. Departing from the

Gulf of Mexico, most of them became seasick and were depleted as the boat twice

nearly capsized in rough waters. Then, after crossing the Caribbean Sea, they

missed their landing spot on the Cuban coast, ran aground in a swamp, and had

to wade ashore in chest-high water. Needless to say, the would-be

revolutionaries were sitting ducks for the defenders.

The

leader of the unlucky band, Fidel Castro, an exiled revolutionary, was reportedly

killed, but he actually made it off the beach and into the mountains along with

some 20 survivors to fight again another day. But in late ’56, the Guardian wrote the expedition off with

the sardonic line that the “invasion fleet” (the yacht) “was badly damaged and

might be unfit for charter for the rest of the tourist season.”*

I

had reached the mess hall food line, laughed off the Caribbean caper, and gave

neither Fidel nor Cuba any further thought. Afternoon classes awaited, and it

was back to the Cold War. But to my surprise, Cuba briefly reappeared on my

radar just over a year later while I was serving in the forces in West Germany.

On an off-duty weekend, I had covered the German Grand Prix – an international

Formula 1 car race in the Eifel Mountains – for an American paper.

It

was an exciting, closely contested race at staggering speeds – won by the

reigning world champion, the Argentine Juan Fangio at the wheel of a Maserati,

edging out his British challenger in a Ferrari by a margin of three seconds. I

filed my story stateside and it was again back to the Cold War. So much for the

glamorous world of F-1 racing.†

But

then, El Maestro Fangio, whose name was usually found on the world’s sports

pages, turned up as front page news in the Paris

Herald Tribune. He had gone to Havana in ‘58 for the Cuban Grand Prix to

defend his title and was ‘politely’ kidnapped by the Fidelistas – by then a

formidable guerrilla movement with broad support, they constantly tweaked

Batista’s forces in classic hit and run encounters.

They

held Fangio just a few days to garner maximum international publicity. When

released unharmed, the champion spoke favorably of his captors, a propaganda

coup for Castro. He had shown he could snatch a world famous figure right off

the streets of Havana with impunity, a sure sign the regime was on its last

legs.

Later

that year I got out of the Army and was back in college, just in time for fall

semester at Brandeis University outside Boston. My father had gone bust

financially, so I was on my own, on borrowed money for tuition and working

nights as a cabbie for Boston Checker. To be closer to my job and because it was

a cool place, I rented inexpensive digs on Eliot Street just off Harvard

Square, Cambridge.

While

I was settling back into the world of books and classes, Castro and his

revolutionary army finally defeated Batista. Entering Havana as victors, they

took power on New Year’s Day ’59. The old regime had been notorious for its

cruelty and corruption, so the Cuban Revolution was greeted warmly by Americans

as well as Europeans, not to mention the Communist Bloc and Third World

nations.

_________________________________________________________

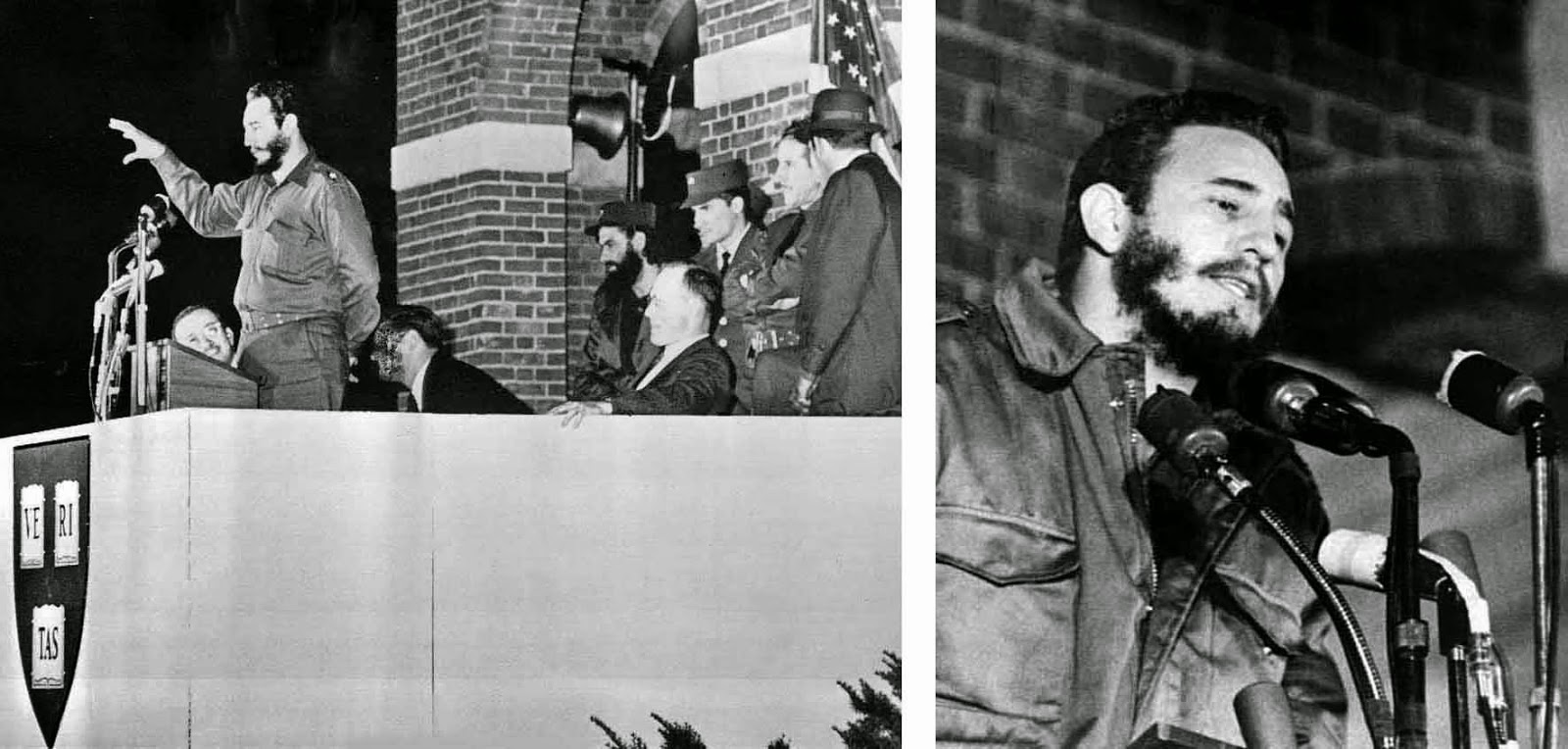

At

Harvard I was in the crowd of 10,000 exuberantly welcoming Castro.

_______________________________________________________

Several

months after the victory Castro was invited to the States. Landing in

Washington – although coolly received by the Eisenhower (Ike) Administration –

the charismatic Maximum Leader took the country by storm, making his way up the

East Coast city by city in a triumphant tour. Castro looked and acted the hero,

and the American public took to him.

Not

everyone was happy about his visit though – there were death threats at every

stop. As a result, when Castro reached New York, the city organized the

greatest security cordon in its history, even more so than for a president. His

final stop in the US was Boston where he was scheduled to speak at Harvard. I saw the posters in Harvard Square and

decided to go hear him.

It

was late April ’59 – actually 55 years ago this week – when Castro appeared at the Harvard Field House on a warm

Saturday evening. After a bomb scare in New York, Boston was taking no chances.

The Cuban leader’s train had been met at Back Bay Station by 300 of the city’s

finest. As he was driven the several blocks to his hotel, cheering crowds

lining the route were held back by a wall of blue.

______________________________________________________________

Cuba’s Ethan Allen leading the Green Mountain boys had taken on and defeated King George III in the guise of Fulgencio Batista.

Cuba’s Ethan Allen leading the Green Mountain boys had taken on and defeated King George III in the guise of Fulgencio Batista.

____________________________________________________________

A

few hours later, Castro was accompanied to Harvard by a combined force of

Boston cops, Metro police, State Department security, and the FBI. As he walked

across the grounds of the field house complex, he was flanked by a phalanx of

tall Massachusetts State Troopers in their sky blue jackets, jodhpurs, and

black boots.

Castro being

escorted by Massachusetts State Troopers, 1959

I

drove down Boylston Street to the Charles River, crossed the Eliot Bridge, and

walked on up Soldiers Field Road to the field house. There I found myself part

of an enormous crowd of some 10,000 students and others exuberantly welcoming the

Cuban leader. He took the salute from a speaker’s stand high above the field

where we all stood.

Harvard

Law School was his host – Fidel was educated as a lawyer – although he was

introduced by the Dean of Harvard College, McGeorge Bundy. It turned out that

Fidel had applied to the law school as a young man in ‘48, but was turned down.

Dean Bundy made light of this, saying that Harvard wanted to make amends and

would now accept him.

Cuban

and American flags were on display, and Castro was decked out in his trademark

olive-green military fatigues and field cap. Standing at the podium above the

Harvard crest, he was unobtrusively shielded on both sides by personal

bodyguards and Boston security. When he was introduced, the roar of the crowd

was deafening – Fidel and the guerrillas were seen through the prism of

American legend. Cuba’s Ethan Allen leading the Green Mountain boys had taken

on and defeated King George III in the guise of Fulgencio Batista.

Castro speaking

at the Harvard Field House

Fidel

was a forceful rather histrionic speaker given to dramatic gestures. His

remarks were billed as ‘The Cuban Revolution’, but he didn’t dwell long on past

battles. Instead he gave a thoughtful, albeit rambling, speech on the problems

of backwardness and underdevelopment plaguing revolutionary Cuba.

From

the press, he well understood that Americans, in their enthusiasm for his victory

over a dictatorial regime, were expecting democracy and the rule of law to

follow, but he patiently explained the more immediate problems facing his

government were hunger, mass illiteracy, and a level of unemployment greater in

scale than during the American Depression.

Castro

went on to say all things would come in due time, but for now elections –

absent political parties – would have to be put off at least two years. And he

added pointedly that rights of the criminally accused would have to wait until

the revolution dealt summarily with the many who had administered the terror

and carried out torture under the old regime.

Up

to that point, he still had the majority of the audience with him, but then a

law student called out a question about a recent criminal case in Havana. A

couple of Batista’s pilots had attempted to bomb the presidential palace. They

received a stiff prison sentence, but Castro, dissatisfied, ordered a retrial.

Second

time around they got the death penalty.

Wasn’t

that double jeopardy the questioner persisted? Castro bridled at the challenge,

responding aggressively that the second trial was justified by the higher right

of the revolution to defend itself. At that, a chorus of boos floated up from

below.

Fidel

grew visibly angry, and his speech dissolved into a rant as he occasionally

slipped from English into Spanish. The crowd’s good will toward him began to

ebb. The atmosphere in the field house complex had changed, and the evening

ended on a down note for many there.

I

went off to grad school a year later. Indiana University (IU) had given me

fellowship money to study Soviet Russia. As it happened, brother Jeff also

arrived in Bloomington for his Freshman year. I was delighted with the lively,

competitive graduate school milieu – in the midst of the Cold War, Soviet

Studies was the hottest field around.

Jeff,

however, was unhappy at the university. He had graduated from a small Eastern

prep school and felt lost on the vast campus, a virtual small city in itself.

He had hoped to go to an Ivy League school where all his friends were, but

Pop’s business reversal precluded a costly private college.

One

of my friends in the Russian Institute was George Shriver. Like me, he had come

out to IU from the East – from Harvard where he’d majored in Russian. While I

was in the Political Science PhD program, George’s focus was Russian language

and literature. Although I didn’t realize it at the time, George was also a

left political activist.

At

IU that fall he had quietly organized a campus chapter of the Young Socialist

Alliance (YSA), the youth affiliate of the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party

(SWP). Then, from the small band of campus Trotskyists, George also spun off a

local branch of the national Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC) in support of

the Cuban Revolution.

George Shriver

speaking at an YSA meeting, Indiana University

As

fall term ‘60 was coming to an end, George, as FPCC chair, was organizing a trip

to Cuba over Christmas break. Jeff got wind of the trip and put his name down,

but even though the cost was modest, he didn’t have the money. He wrote home

for funds. While our parents were apolitical, they were wary of anything

controversial when it came to their sons, so Jeff had to make a persuasive

pitch since the US government considered Cuba leaning toward Communism.

Yet to come, the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion was an open secret in Miami émigré circles, and Castro’s forces were more than ready for them.

____________________________________________________________________________________

Yet to come, the ill-fated Bay of Pigs invasion was an open secret in Miami émigré circles, and Castro’s forces were more than ready for them.

__________________________________________________________

In

his letter, he explained that the trip was sponsored by FPCC, a national

organization dedicated to offsetting critical media coverage of Cuba and giving

the revolution a fair shake. He added:

The Cuban government wants Americans to come there and judge the situation and the results of the revolution for themselves. There is nothing political involved. It’s just to have a good time and get informed on the real situation in Cuba.

Jeff

asked me to add an endorsement to his letter, which I was happy to do. I knew

he was drifting at IU and was glad to see him finally taking an interest in

something.

Apparently

the parents were persuaded, but in the end Jeff never made it to revolutionary

Cuba. There weren’t enough takers, so the trip was called off. Not long after he

dropped out of school and a year later found himself in my old military outfit.

However, instead of sailing off to Europe as I did, he was taught Vietnamese

and landed in Southeast Asia in the middle of a small war.

But

I’m getting ahead of the story. By that spring of ’61 Cuba was back in the

headlines. The time was JFK’s first 100 days, and he had adopted Ike’s animus

toward Castro and, worse, his predecessor’s misbegotten plan to remove him from

power – another hamhanded invasion of the island by Cuban exiles – although this

time not a revolutionary vanguard, but a brigade of CIA-trained anti-Castro

‘patriots’.

Once

again McGeorge Bundy, by then JFK’s National Security Advisor, was out front –

serving as White House liaison to the Agency’s invasion planners. The ensuing

Bay of Pigs fiasco is well-known – the whole ill-fated enterprise had become an

open secret in Miami’s Cuban émigré circles, and Castro’s forces were more than

ready for them.

The

operation was a personal tragedy not just for the hundreds of brigadistas who

survived, languishing in harsh Cuban prison camps for nearly two years – it was also a political disaster for America’s new young

president. However, the image of his administration as a bunch of bunglers and

himself personally as lacking in resolve only steeled JFK’s determination to

get Castro. One of the President’s favorite maxims was ‘Don’t get mad, get

even’.

After

purging senior CIA people responsible for the debacle, JFK tasked the Agency to

covertly eliminate Fidel – in a word, assassinate him. The hit plan, code-named

‘Operation Mongoose’, enlisted Cuban émigrés again, but this time the American

Mafia as well – the very guys whose Havana casinos had been seized by the

Castro regime in ’59.

By

summer ’62 the bizarre plotting to decapitate Communist Cuba was well

underway. Some of the looney ideas the plotters

came up with included a lethal exploding cigar, exposing Castro to a fountain

pen treated with poison, and, perhaps looniest of all, slipping a chemical into

his shoes to cause his signature beard to fall out – that wouldn’t have worked

anyway.

Unbeknownst

to the US, that very summer Khrushchev was planning clandestine operations to

carry out regime change in Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador, Latin American

dictatorships firmly in the Western camp.

However,

sensing that Kennedy might attempt another attack on Cuba, Khrushchev changed

his mind and decided instead to secretly reinforce his new Caribbean client state,

a move which would erupt in the coming months into the Cuban Missile Crisis –

arguably the most dangerous moment of the long Cold War – but that’s a story

for another post.

____________________________________________

*Manchester Guardian (December 4, 1956).